As reminded by a good friend, I made sure to enter the GDFS Poster Competition this year, alongside two of my favourite posters of the past I created a bespoke poster for just this competition because I felt the desire to produce something I've never done before.

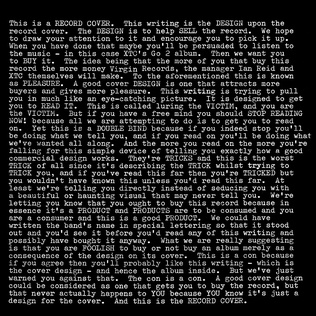

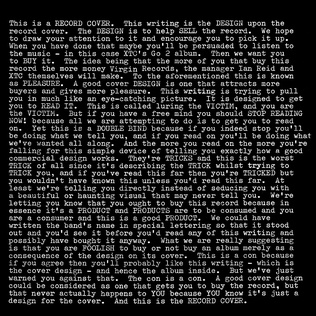

If you've ever been here before, you'll know I like two sections of design quite a lot—writing and posters. I've never really mixed the two and I've honestly never seen anyone else do it to a manner that I would deem interesting either, so why not give it a crack ey? I didn't want to just repurpose one of my writings onto a poster as that felt a little cheap; I wanted to make something that I didn't think they'd receive twice this year, that being a poster that holds an essay seeking to define the purpose and definition of the item it's laid upon.

I spent a few evenings with beer and musings to create this poster, in the manner I often do for just these blog posts; but unlike these, I did not want to create any visual excitement to the poster—leaving it obviously bland to focus upon its words and it's juxtaposition. In these posts, I use imagery and GIFs to break up the writing and give you a quick woo of excitement but that's not what I wanted of the physical poster, wanting its absence of visual excitement to be poignant.

See the poster and its essay below.

|

| You may need to zoom into this one. |

What defines a poster? Officially classed as any item produced to create awareness through distribution and visibility, the poster is synonymous with a portrait printed page, found in shop windows, peeling from brick walls and in every live music venue ever. There is little that defines what a poster can or cannot be, but for the main part if you were to be presented half-masticated chewing gum on a post-it note; you would not instantly define it as a poster, but if used to be displayed in an attempt to raise awareness about chewing gum—by definition it is now a poster.

We typically regard the A3 printed page, as the standardised poster, though even changing this format from portrait to landscape instantly transforms the standardised poster format into an oddity. Anything above the size of A3 in ratio could be easily described as a poster from a great distance, but once this format reaches A5 or smaller we would regard the same information as a flyer. It's possible that we attain the definition of the poster to something we post thus defining it as something not particularly suitable for handing out or distributing by hand, like a flyer. When scaled to that the size of a billboard, we still observe the printed pages to be a poster but don't name it as such—the poster as we understand it exists in its familiarity, it's expected format and unspoken rule for the ratio.

If not defined by its dimensions, we often seek the expected hierarchy of Heading, Sub Heading, Date then content—this can be balanced differently with opposing and supporting imagery but the formula for the most effective information broadcast stays the same. Without the hierarchy we desire, does a poster cease to be a poster for it's not effectively transmitting the message or statement that it's assigned to do? It's possible that the lack of hierarchy could make a poster more effective (see the current one you are reading) when seen in juxtaposition to what we expect when our eyes clock onto the strict ratio of 1:1.4.

Even when removing the hierarchy to the best of your ability it's still impossible to be void of its concept, there is still a clear structure to the writing and the title is bolded (by choice) to define it from the main body of the writing. It's traditional to have a little text as possible upon a poster to make the content as easily digestible as possible, but confronted by this wall of text I doubt that you have been struck by the concept that what you are gazing upon is not a poster; whereas the existence of this poster stands against the conformity we expect of them.

If the technically defined purpose of the poster is not being met, then what purpose can be expected of a poster to this ethos? In the context of a design competition, a poster subverting the norm is perfectly acceptable but in a street, serving the purpose of awareness this would not have any legs to stand upon, both metaphorically and physically—it's paper after all people. Gosh.

For the sharp-eyed viewers or the people who are have allowed themselves the extra 30 seconds to reach this far into the amateur essay, printed enlarge on a flat displayed service for your reading pleasure; you may realise that the idea I'm exploring here isn't totally original. The 'making a large statement through subverting the expected using a large body of text on a black background' isn't in fact as original as I wish it was, it was actually employed by the band XTC in 1978, designed by the infamous Hipgnoisis for the album sleeve of Go 2. This statement is in full admission that the idea of the visual discourse of this poster has been derived from that source, like a highland stream of post-post design ideas.

In the internal ever rotating existence of the poster, the concept of ideas is a bizarre topic to dissect especially when the visual essay doing said incision is actually repurposing a rather famed idea to promote its message. It's poignant to assess the concept of ideas when also asking what defines a poster, as we only define something as a poster due to it having a descended idea from that of a similar item from the past. When we understand the current discourse of a poster from the ideas they've present in the past, is it fair to define what can and cannot be a poster—especially when we operate in an industry, now ever more evenly split between print and digital.

Now confronted with the question of what defines a poster and where the ownership of ideas and concept can sit, how can we then define the poster or even the idea for its format when we've radically leapt forward into the digital sphere after perpetually existing in a historical powerhouse of print. The terms of Print is Dead and Print is not Dead are thrown around, arguing the ground for both, with the latter most likely being supported by the poster economy like Atlas supporting his globe. As posters are beginning to create a market for themselves, reviving the print market with an ink based defibulator—but how do we define a poster in a digital space when we know what we expect of one in a tangible printed form.

We look upon a digital image and at the point of recognising it's 1:1.4 ratio we'll likely understand it to be a poster but when that is subverted, does it lose the right to it's poster definition? Does posting something digitally allow it to still be defined as a poster, even when the definition of poster comes from the physical act of posting something upon another surface? Does the ratio of the post also become irrelevant when we share a poster into a digital space like Instagram, with it's forced square ratio?

In the case of art, I believe that if something is created to be an artwork then we can define it as art rather than something being created then called art post-existence. If we create a piece of design in the aura to be a poster, does it become justified to be named a poster if it isn't physically posted or even in the ratio that we thrive to define it into, or even the hierarchy we search for?

It is known that posters are unlike buildings or sculptures for in both physical and digital instances, we understand a poster to be an ephemeral object, serving its purpose for a defined amount of time. This was originally a constriction brought upon the poster through its usage and materials, but now as we have an expansive digital space we may still treat the digital posters as ephemera but unlike paper and other decomposing resources of the physical poster it has the ability to last possibly forever, until our eventual cyber inhalation.

Now knowing that posters do not need their physicality, ephemeral existence or even the hierarchy we desire to be defined as a poster; it's worth asking what cannot be defined as a poster. If you are reading this in a physical sense, stood in a gallery or upon a street then it proves that even this self-evaluating monochrome image can be defined as a poster, judged by the poster judges that be. I hope that this series of questions, statements and wild contemplation have not felt like a waste of your time and that if you find this 'poster' surrounded by lots of other printed pages in a 1.14 ratio—you'll now analyse their existence in comparison to what you've found here.

Like many entities that exist in this world, we cannot define anything with a simple set of rules and the definition of design's hot ticket item – the poster – certainly cannot be put into the easy to define the category. So to conclude, what does define a poster?

You.